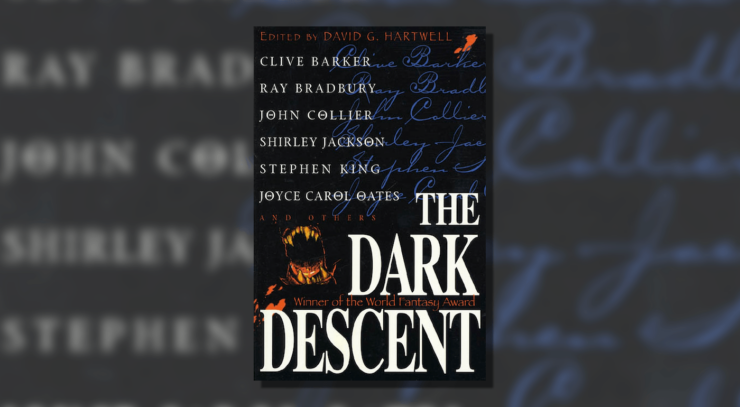

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For a more in-depth intro to the series, check out the first installment.

It cannot be overstated exactly how much Hartwell picked a winner with John Collier’s “Evening Primrose.” It’s a strong morality tale by a master of deeply unnerving stories whose work has mostly fallen by the wayside (a reprint of Collier’s collection Fantasies and Goodnights is practically all that remains of his short work, as well as two ebook editions of his novels). Which is a shame, because Collier has been, and arguably still is, deeply influential.

And not just in the short term—though his work served as a font of inspiration for roughly forty years after its immediate publication: “Evening Primrose” on its own inspired both a suitably dreamy hour-long Sondheim piece starring none other than Anthony Perkins (and who knew Norman Bates had such a lovely tenor?) and the deeply unnerving Twilight Zone episode “The After Hours”—but in the long term, as well. Its DNA can be found in everything from liminal horror favorites like the Backrooms, to horror-themed critiques of capitalism, to numerous Gothic-flavored stories about toxic and obsessive men.

As always, for those of you who don’t have a copy of the story handy, a quick synopsis. “Evening Primrose” is told in journal entries from the point of view of Charles Snell. Snell, a self-described poet, drops out of normal life and instead opts to nest behind the rugs in a department store, venturing out at night for clothes and food. To his shock, he’s dragged into a whole society that had the exact same idea, ruled by the terrifying (and barely human) Mrs. Vanderpant and a group of animate shadows. As Snell adapts to his new society, he falls in love with Ella, a young woman serving as Mrs. Vanderpant’s maid. It’s through her that Snell learns of the terrifying “Dark Men,” creatures of living shadow who turn burglars and rule-breakers (and anyone the dwellers simply dislike) into mannequins and put them on display in the store. Snell must carefully balance the strictures of his new life with indulging Ella’s thirst for the outside world, but his burgeoning love for Ella threatens to throw everything into disarray as they risk becoming the newest residents of the department store’s display window.

As seen through Snell’s eyes, the store is lavish, but also perfectly eerie. Collier is good at describing rooms full of people and objects that somehow feel unnervingly empty in the perpetual nighttime of the store dwellers. At times, the whole place operates on nightmare logic—Mrs. Vanderpant is described as “almost transparent,” the denizens of various stores around New York are unable to leave once they’ve put down roots and never seem to die, and the “Dark Men” are insectile necrophages who dwell in a mortuary. It’s a world described as “half-lit,” where the outsiders “stink of the sun,” a network of places that feel haunted and empty in the way stores and buildings do when they’re no longer in use. Collier even plays with both sides of the line when it comes to liminal horror, giving us Snell’s odd recollections of his half-lit world as he adjusts to its unusual denizens and routines, and also showing what those kinds of spaces are like from the point of view of the lurkers well accustomed to those spaces.

But as much as Collier writing in Snell’s voice captures the haunted feel of monuments to capitalism where capitalism isn’t taking place, part of what makes the story work as a moral allegory is how terrible a human being Charles Snell truly is. He’s the kind of person who abandons the world solely because they couldn’t recognize his genius, sneers at the people he’s abandoning to hide out in a department store, and openly believes himself to be the main character of his situation just because he’s only considering his own point of view. With his purple prose, poisoned worldview, and existence in a purely nightmarish situation, Snell reminds one of the toxic men found in works like Ligotti’s Songs of a Dead Dreamer and other modern short stories featuring “sensitive artists” who use big words and their own self-importance to try and cover for their multitude of sins.

While flashes of this are seen in the hypocritical way Snell flagrantly claims to eschew society even while living parasitically in a veritable monument to capitalism, this is most clearly illustrated in the way Snell pursues Ella, presumably the only woman in “Evening Primrose” who isn’t a senior citizen. He immediately views Ella as something of a child, an ingenue he can easily influence and dazzle with his worldly and artistic nature. He dotes on her, promising her they’ll see birds together and getting her little gifts that, despite Ella’s clear rejection of the department store, come from the store itself with minimal effort on his part. Even the terrifying climax of the story, where the Dark Men finally descend upon the store, is a result of Snell’s self-absorbed attitude.

When Ella repeatedly rejects his advances in favor of a distant relationship with the store’s night watchman, Snell rats her out. He claims in the journal he wasn’t thinking when he “lets things slip” to his friend Roscoe, but by this point we’ve spent enough time with Charles Snell to know otherwise. He’s a person who acts purely in self-interest and doesn’t even begin to think about the larger impact his self-interest will have on others. This was true even before Ella claimed she saw him as a friend, when after what he saw as a grand romantic gesture, he goes to kiss her and she turns her head to offer her cheek. The story ends with Snell about to commit a stupidly self-sacrificing act to deal with his guilt over Ella, not so much to redeem himself but to resolve his own internal feelings at the horrors he’s caused.

It’s both these elements—the lavish yet liminal look at capitalism and hypocrisy combined with the narrative of a toxic man who (bucking the usual stereotypes of toxic men whose minds inevitably turn to violence in the majority of works) never commits a violent act but still has to face the consequences of his own morality—that make “Evening Primrose” feel so refreshingly modern and ahead of its time. Its cheerfully grim take on the traditional Gothic hero and ingenue stereotypes, the bizarre feel of the department store setting, and the ruthless satire of capitalist excess call forward even to works being produced in the modern day.

Finally, it fits perfectly within Hartwell’s idea of the moral-allegorical horror story and its place in the “first stream” we discussed last time. It’s a story with a clear moral center, unnerves the reader while asking some tough questions about modern society, and the fact that it still feels so fresh and of a piece with more contemporary works is only further proof that it belongs here. Given our discussion two weeks ago on how important order is, I almost wish Hartwell would have started with this story, a definitive example of his statements on horror. Collier’s important to the history of horror as a whole with his cruel but forward-thinking satire, and Hartwell’s instincts were on point with this one.

And now over to you—let us know your thoughts on “Evening Primrose” and Collier’s legacy in the comments…

In two weeks: We get a little more traditional and gothic with M.R. James and “The Ash Tree.” See you then!

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.